For too long, governments have accepted beliefs about the housing market which have led to policies that have not appropriately addressed the issue of housing unaffordability. These myths have been reinforced through mainstream and social media and are widely accepted as true. But are they?

Here we address two of these housing myths and examine two practical solutions that will help provide more housing and chart a return toward a more affordable housing market.

Myth #1: Foreign investment is the main cause of housing price escalation

There is no doubt that foreign investment exists in the housing market (remember British Properties?), and for the foreseeable future, it will be there.

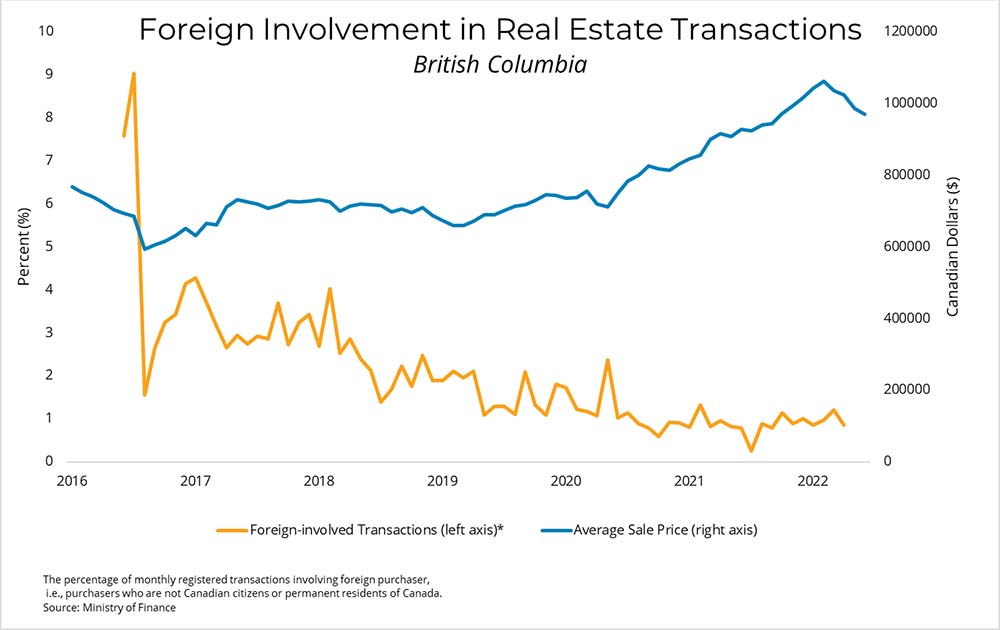

Over the past six years we have seen a steady reduction in foreign investment in the real estate and throughout that time prices have escalated at an unprecedented rate. Over the past year, the market value of foreign investment is only about 0.3 per cent.

There is no doubt that foreign investment exists in the housing market (remember British Properties?), and for the foreseeable future, it will be there.

Over the past six years we have seen a steady reduction in foreign investment in the real estate and throughout that time prices have escalated at an unprecedented rate. Over the past year, the market value of foreign investment is only about 0.3 per cent.

Myth #2: We’re building enough housing

It’s bad methodology to compare population growth and housing stock to conclude that we have been building enough housing. Demand for could far outpace housing stock, but if there isn’t enough housing then population could still stagnate, or even decrease.

Housing stock/new supply is a constraint on population growth – people can’t move/stay here if there’s nowhere to live. More than 100,000 people moved to BC in 2021, approximately 34 per cent from other provinces/territories and the rest from other countries (Source: Province of BC).

Here are some additional facts to consider:

A report from CMHC said B.C. as a whole would require 570,000 new homes beyond what is usually built to achieve anything resembling affordability by 2030. That figure represents over 71,000 new units per year, every year between now and 2030, over and above currently projected housing growth.

A recent Scotiabank housing report stated that Canada has the lowest number of housing units per 1,000 residents of any G7 country. The number of housing units per 1,000 Canadians has been falling since 2016 owing to the sharp rise in population growth. An extra 100,000 dwellings would have been required to keep the ratio of housing units to population stable since 2016—leaving us still well below the G7 average.

Average household size has been declining, so we need more housing stock. Most municipalities have not met their housing growth projections. In Metro Vancouver, only North Vancouver City has seen new housing completions above their projections from the Regional Growth Strategy. Metro Van as a whole is 6% below its own projection (Source: Homebuilders Association Vancouver).

Real Solutions to Improve Housing Supply

Improving the new housing approval process

It takes too long to bring new housing from concept to market. For an apartment building, a five-year period from initial project proposal to occupation is not unusual. The public consultation model is broken – we need a better process for public hearings.

A solution is to strengthen the Official Community Plan (OCP) with zoning powers – new proposals compliant with the OCP should jump straight to the development permit stage. There is no need for a time-consuming rezoning and public hearing process for a development that adheres to pre-established community housing priorities.

A major benefit of this structure is that it would front-load the process for special interest groups to voice their opinion on community housing priorities during the development process of the municipal community plan. This is a better time for these voices to be heard and for communities to then make decisions and chart a path using their OCP. This change would maintain a democratic community development process while also eliminating the major development delays caused by additional community meetings. It would streamline processes significantly for the better.

The public consultation at OCP approval stage encourages public feedback on a community-wide, longer-term perspective, instead of a “single-property, short-term, how-does-this-impact-me” approach, which favours special interest groups intent upon slowing down or stopping new housing supply in their neighbourhood.

It is essential that any supply solution follow the advice of the provincial Development Approvals Process Review (DAPR) and the BC-Canada Expert Panel on the Future of Housing Supply and Affordability. Both studies identified the municipal approval process as a significant barrier to the ability for housing supply to respond to spikes in demand.

It’s bad methodology to compare population growth and housing stock to conclude that we have been building enough housing. Demand for could far outpace housing stock, but if there isn’t enough housing then population could still stagnate, or even decrease.

Housing stock/new supply is a constraint on population growth – people can’t move/stay here if there’s nowhere to live. More than 100,000 people moved to BC in 2021, approximately 34 per cent from other provinces/territories and the rest from other countries (Source: Province of BC).

Here are some additional facts to consider:

A report from CMHC said B.C. as a whole would require 570,000 new homes beyond what is usually built to achieve anything resembling affordability by 2030. That figure represents over 71,000 new units per year, every year between now and 2030, over and above currently projected housing growth.

A recent Scotiabank housing report stated that Canada has the lowest number of housing units per 1,000 residents of any G7 country. The number of housing units per 1,000 Canadians has been falling since 2016 owing to the sharp rise in population growth. An extra 100,000 dwellings would have been required to keep the ratio of housing units to population stable since 2016—leaving us still well below the G7 average.

Average household size has been declining, so we need more housing stock. Most municipalities have not met their housing growth projections. In Metro Vancouver, only North Vancouver City has seen new housing completions above their projections from the Regional Growth Strategy. Metro Van as a whole is 6% below its own projection (Source: Homebuilders Association Vancouver).

Real Solutions to Improve Housing Supply

Improving the new housing approval process

It takes too long to bring new housing from concept to market. For an apartment building, a five-year period from initial project proposal to occupation is not unusual. The public consultation model is broken – we need a better process for public hearings.

A solution is to strengthen the Official Community Plan (OCP) with zoning powers – new proposals compliant with the OCP should jump straight to the development permit stage. There is no need for a time-consuming rezoning and public hearing process for a development that adheres to pre-established community housing priorities.

A major benefit of this structure is that it would front-load the process for special interest groups to voice their opinion on community housing priorities during the development process of the municipal community plan. This is a better time for these voices to be heard and for communities to then make decisions and chart a path using their OCP. This change would maintain a democratic community development process while also eliminating the major development delays caused by additional community meetings. It would streamline processes significantly for the better.

The public consultation at OCP approval stage encourages public feedback on a community-wide, longer-term perspective, instead of a “single-property, short-term, how-does-this-impact-me” approach, which favours special interest groups intent upon slowing down or stopping new housing supply in their neighbourhood.

It is essential that any supply solution follow the advice of the provincial Development Approvals Process Review (DAPR) and the BC-Canada Expert Panel on the Future of Housing Supply and Affordability. Both studies identified the municipal approval process as a significant barrier to the ability for housing supply to respond to spikes in demand.

Allow more types of housing in more places

In most cities, the vast majority of residentially-zoned land only allows single detached homes – the most expensive form of housing.

Zoning reform can allow “multi-plex” missing middle housing (duplexes, triplexes, fourplexes with secondary suites and coach/laneway homes) on most single detached-zoned lots. This will allow for more ground-oriented, family-friendly homes. The ability to distribute the high cost of land amongst several housing units creates improved affordability.

Existing single-detached zoned neighbourhoods are near important infrastructure: schools, parks, recreation centres, libraries, retail/commercial districts and transit.

Many older single-detached zoned neighbourhoods are experiencing population stagnation. Allowing new, young families to move into these areas will generate more school enrollment and provide more support for the small, local retail/commercial businesses that populate local high streets.

With a streamlined approval system, the small-scale nature of these developments means that they can be built quickly, in more areas of our cities. Unlike large apartment projects, missing middle housing can be built by smaller contractors, much like single-family homes.

Smart design can create missing middle housing that is sympathetic to the scale and character of existing neighbourhoods, addressing the concerns of many who oppose this type of housing. Check out the Missing Middle Competition for some great examples of missing middle housing.

In most cities, the vast majority of residentially-zoned land only allows single detached homes – the most expensive form of housing.

Zoning reform can allow “multi-plex” missing middle housing (duplexes, triplexes, fourplexes with secondary suites and coach/laneway homes) on most single detached-zoned lots. This will allow for more ground-oriented, family-friendly homes. The ability to distribute the high cost of land amongst several housing units creates improved affordability.

Existing single-detached zoned neighbourhoods are near important infrastructure: schools, parks, recreation centres, libraries, retail/commercial districts and transit.

Many older single-detached zoned neighbourhoods are experiencing population stagnation. Allowing new, young families to move into these areas will generate more school enrollment and provide more support for the small, local retail/commercial businesses that populate local high streets.

With a streamlined approval system, the small-scale nature of these developments means that they can be built quickly, in more areas of our cities. Unlike large apartment projects, missing middle housing can be built by smaller contractors, much like single-family homes.

Smart design can create missing middle housing that is sympathetic to the scale and character of existing neighbourhoods, addressing the concerns of many who oppose this type of housing. Check out the Missing Middle Competition for some great examples of missing middle housing.

Original article from bcrea.bc.ca